Black — Total destruction

Purple — Damage beyond repair

Dark Red — Seriously damaged, doubtful if repairable

Light Red — Seriously damaged, repairable at cost

Orange — General blast damage, minor in nature

Yellow — Blast damage, minor in nature

Green — Clearance areas

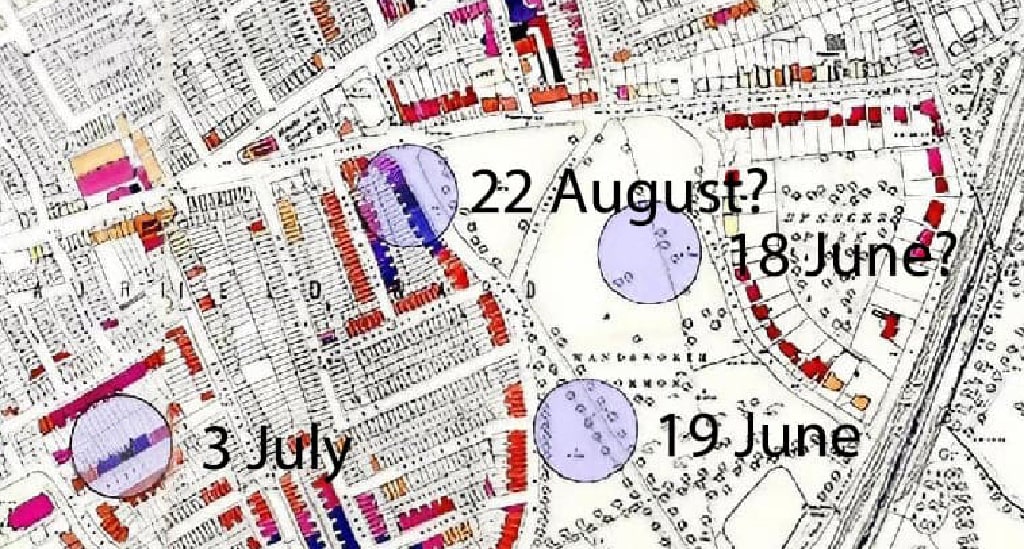

Small circle — V-2 Rocket

Large circle — V-1 Flying bomb

For greater clarity, I've also highlighted the V-1 and V-2 circles pale purple and pink respectively. The original circles were simple outlines.

These maps can be viewed online (to get started, tick "Use this overlay" at the top, then zoom in). They're also available as a single huge volume, edited by Laurence Ward (2015). The base map the LCC used was already out of date, but the latest available at the time.

According to the South Western Star, 15 September 1944:

"Except for a possible few last shots, the battle of the flying bomb has been won . . . "

Oh no, it hadn't.

The reason I'm discussing V-1s and V-2s this month is because I came across a article in the local press from mid-September 1944 that thoroughly perplexed me. It asserted, apparently authoritatively, that the "battle of the flying bomb has been won" — that the aerial war was now over because Britain had found ways of preventing further attacks from V-1 "Doodlebugs".

But as we know, there would be more V-1s — they continued to fall until 28 March 1945, though much less frequently.

And having grown up in a block of flats on Heathfield Road built on the site of a rocket-bomb, I knew there would be a new generation of weapon on its way. This was the V-2 — a quite different beast.

In fact, by 15 September 1944, the first V-2 rockets had already reached London. (The total would eventually be more than a thousand. At 6:37pm on Friday 8 September 1944, a V-2 landed in Chiswick, killing three people (including a three-year-old girl), and injuring nineteen.

But initially, the V-2 rockets were not acknowledged among the more numerous V-1 doodlebugs. The government was so anxious not to alarm people that they talked about V-2 blasts not being caused by bombs at all, but gas explosions. (This led to a cynical public calling the V-2 rockets "Flying Gas Pipes".)

Another reason for discussing bombs in this edition of the Chronicles is that the Blitz started in September, four years earlier (7 September 1940), and it too profoundly affected our area.

Until mid-1944, bombs were always dropped from planes — among them High-Explosive [HE], Incendiary [IB], and Anti-Personnel [AP] bombs, and Parachute Mines [PM]. Some exploded on impact, some when they had descended to a certain height above the ground (which increased the damage caused by the blast), and some with delayed-action fuses that might lie dormant for several days.

From June 1944 onwards, though, nearly all high explosives were delivered by pilotless V-1 flying bombs — the Cruise missiles of their day — or by V-2 rocket-bombs.

As we shall see, many of the post-war houses around the Common were built on bomb sites, which I'm trying to map and date. I'm also trying to collect stories left by eye-witnesses. (If you know of any more, do please get in touch.)

Here is that overly-optimistic article in full, with the locations of bombs that had fallen in the previous three months:

The focus of the article is on Battersea but there are many references to Wandsworth too. (The two metropolitan boroughs were not combined, to form the London Borough of Wandsworth, until 1966.) It is remarkably explicit about the number of bombs, where they'd fallen, and with what effect (including the precise number of deaths caused). I'd always assumed that this sort of info. was deeply hush-hush, in case it alarmed Londoners and told the Germans how successful or otherwise they were being with their murderous new "vengeance" weapons. But no.

Innumerable bombs fell on and around the Common during World War Two. Not every bomb caused destruction and or death, but many did. We can often still see signs of these events today, for example in houses built where the bombs fell.

There is also a long list of local men, women and children injured and killed at this time. Reading through the Commonwealth Graves Commission (CWG) Casualty Search lists for Wandsworth and Battersea and other sources I notice the deaths of people living in many of the roads shown on our map, among them (roughly clockwise from top left):

— "Wandsworth Common Shelter" *

— Tonsley Place, Tonsley Hill

— Huntsmoor Road

— East Hill Estate, St Peter's Almshouses, Spanish Road

— Usk Road, Petergate

— Price's Factory, York Road

— Maysoule Road

— Surrey Hounds pub, St John's Hill, Plough Way

— Vardens Road

— Lavender Hill

— Lurline Gardens, Altenburg Gardens, Lavender Sweep

— Battersea Rise

— Battersea Cemetery

— Bolingbroke Hospital

— Hauberk Road

— Chatham Road

— Balham Grove

— Balham Tube Station

— Kate Street

— Bethany Convent, Nightingale Lane

— Jewish Home of Rest, Birchlands Road

— Nightingale Lane

— Mayford Road, Calbourne Road

— Ravenslea Road

— Boundaries Road

— St James's Hospital (St James's Drive, Sarsfeld Road)

— Hosack Road

— Springfield Hospital

— Anglo-American Laundry, Burmester Road

— Hazelhurst Road

— Swaby Road

— Openview Road

— Tilehurst Road

— Lyminge Gardens

— Earlsfield Road

— St Ann's Hill

— Wilna Road

— Malva Road

— Garratt Lane

— St Ann's Hill, Westover Road

— Swaffield Road

— Barmouth Road

— Allfarthing Lane

[N.B. I've probably missed some — if you know of others, please let me know.

Links point to further references in these Chronicles.

* "Wandsworth Common Shelter", which appears in some lists (though not the CWG's), has probably been confused with Wandsworth Park's, where at least 16 people died in April 1941.

Some roads no longer exist, e.g. Kate Street and Huntsmoor Road.

Sources

— Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Civilian Casualties in Battersea

— Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Civilian Casualties in Wandsworth

— See also Stephen Henden's immensely useful site, Flying Bombs and Rockets, which includes a timeline, background information, stats, recollections, and detailed incident logs analysed by postcode. SW18 and SW17 are missing from Flying Bombs and Rockets website, but he very generously sent me his as-yet unpublished spreadsheets. Thanks, Stephen!]

As I said earlier, I want to look at where the bombs fell, but also at the buildings we see today that were constructed on their sites. To get ourselves started, let's look at a few post-war buildings on the sites of explosions that occurred early in the war, so were not caused by the V-1 or the V-2.

In some cases, bombed buildings were repaired or totally reconstructed exactly as before — Wandsworth Common Station is an example:

But in many cases, there are few if any clues what their predecessor buildings were like. They have been totally erased, largely forgotten.

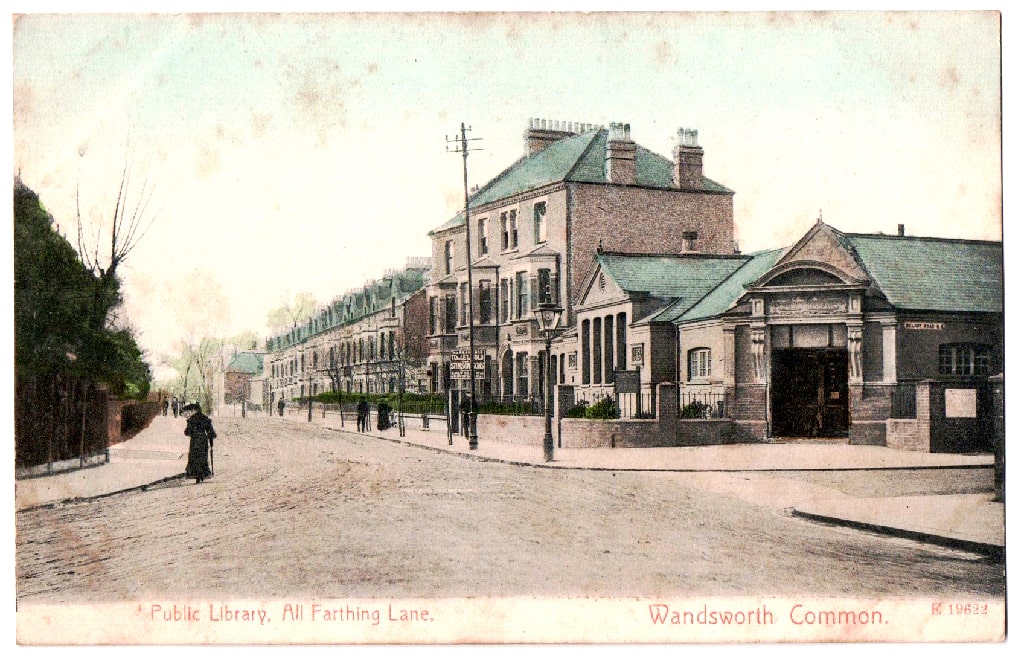

Here's a postcard of the old library at the top of Allfarthing Lane, facing the Common, photographed around 1910:

A new library was built on the site, and then a block of flats erected behind/above it. That would have been late-1950s, I think.

[How I loved that new library! Very modern, very bright, very comfortable. And above all chock full of new books. My first library, which I also bless, was at the bottom of Magdalen Road. But Alvering is where I was first allowed to borrow from the grown-ups section.

About 2008, to my deep disappointment, this beautiful library was sold off to a private nursery school — another public asset lost. Grrr.)

It would be good tell the story sometime of the origins of the old library, with its mix of private philanthropy, thirst for popular education, and municipal pride.]

After the war, very different buildings generally replaced the sometimes quite substantial houses that had been destroyed.

For example, here are views of two small blocks of flats, of similar design, built on Baskerville Road. Both back onto the Common:

Another bomb had fallen a few doors along, at16 Baskerville Road:

[Hmm, doesn't that imply there were originally two houses on the site, not one?]

There are other examples (for example, along Bolingbroke Grove), but these will have to wait for the moment. Now let's turn to the V-weapons in 1944-1945.

The "V" in V-1 and V-2 is short for Vergeltung — German for Vengeance, Revenge or Retribution. The first of this new generation of pilotless terror weapons fell on Grove Road, Bow, at 4:25am on 13 June 1944. This was a week after D-Day, when the Allied invasion of Normandy began the effective fight back. A railway bridge and nearby housing was destroyed, and six people were killed.

The first V-1 to land on our area came four days later, 17th June, falling between the Surrey Hounds pub and the Granada Cinema on St John's Hill.

The V-1 flying bomb demolished the Surrey Hounds pub, shops and a number of houses. One person was killed — far fewer than might have been expected — but many more were injured. Two passing buses were badly damaged — it looks to me that all their windows were blown out. Were many of the injured on those buses, or had the air-raid warning alerted the passengers to seek cover?

[I have a number of fascinating eye-witness accounts of this event but I think I'd better discuss these another time.]

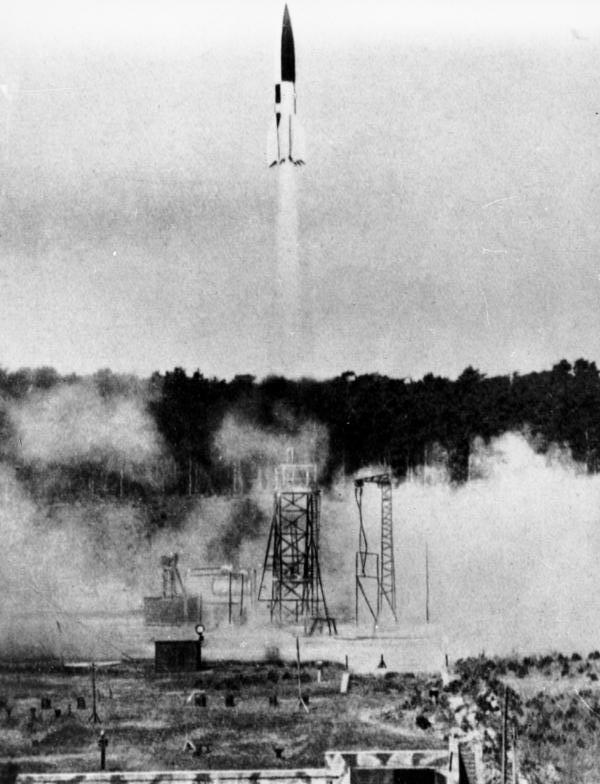

Here's a V-1:

The first person to hear the new V-1 rocket-bomb, an observer on the North Downs, described its sound as "put-put-put". Irene Caudwell, who we'll be hearing more from later, describes the ominous noise as a "chug-chug-chug":

". . . of all the horrors of those nerve-racking years, the worst was the flying-bomb, with its rhythmic "chug-chug-chug," followed by a sudden silence in which the world seemed to stand still, waiting for the explosion with its accompanying death and destruction."

Here's a description from another South Londoner:

"The most noticeable aspect of the doodlebugs was their sound, which was quite unlike any ordinary plane; it had a strange tearing and rasping sound, more like a two-stroke motor-cycle.

It soon acquired a sinister and disturbing quality, and prompted ignoble reactions. If the motor cut out when the weapon was approaching, then it was likely to drop nearby and one tried to take shelter; if it continued its flight, one could feel relieved: someone else would be the victim.

[Time Witnesses: Ben's Story.]

The V-1 missile carried a 1,870lb (848 kilo) warhead. Between June 1944 and March 1945, over 9000 V-1s were launched against England — about thirty a day. A total of 2,419 landed on London, killing 5,125 people (roughly two per V-1 explosion):

And here's a V-2:

Neither V-1 nor V-2 could be aimed with any precision. V-1 engines typically cut off after a set time, or when they ran out of fuel, then dropped more or less at random. V-2 rockets were ballistic missiles. They just went up up up into the stratosphere, then came down down down anywhere within a circle many miles across. On impact, they were travelling at around 2000mph.

Curiously, the fact that the accuracy of both V-weapons scarcely improved over time may partly be explained by the success of "Spycatcher" Lieut.Colonel Oreste Pinto working in the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building.

Pinto and his team, who interrogated nearly every foreign national entering Britain, are credited with spotting all potential German spies — hence accurate information about where exactly they were landing never returned to control centres in Belgium and Holland. It is said that false information was also deliberately spread about impact sites, so more V-2s were misdirected and landed in areas of lower population densities.

— here's a newspaper article about one of Lt. Col. Pinto's successes at the RVPB: "Three men who gave the Cabinet jitters".

There is an enormous literature on V-weapons, including:

— Wikipedia: V-1 Flying Bomb.

— Wikipedia: V-2 rocket.

— Imperial War Museum: The Terrifying German "Revenge Weapons" of the Second World War. (Good summary, with excellent audio.).

— On the use of double agents to return misinformation about where V- and V-2 bombs were exploding, see e.g. Wikipedia: Double-Cross System [thanks for the reference, Marc!].

Here, the glorious Tom Lehrer sings of Wernher von Braun, the German aerospace engineer who was the principal architect of the V-2 rocket-bomb — and later a tireless lobbyist for spaceflight when he was scooped up by the US after the war:

— Tom Lehrer: Lyrics to "Wernher von Braun".

So far, by focusing on the physical buildings I've been ignoring the people who lived (and in many cases died) there. I very much want to find out more about who had lived on or near these sites, and if possible to retrieve personal accounts.

(What follows is just a start. If you can point me towards further sources, I would be very grateful.)

In her marvellous memoir Four Miles from Charing Cross, Earlsfield Road-resident Irene Caudwell writes:

A typical morning during the flying bomb season was while out shopping I had to take shelter three times; on the first occasion the grocer grabbed me by the arm and pulled me into a little dark cubby-hole at the top of his cellar stairs; the second bomb to arrive found me talking to the Sister-in-Charge of the Church Army hostel, who hurried me into the basement into her store cupboard, where we sat amid jams and pickles until the evil thing had passed us by.

The third caught me alone in the church [St Anne's] as I was attending to my sacristan duties in the vestry. This one passed directly overhead, sounding as though it were just coming down. I dived under a pew and lay flat literally in the dust . . .

It was a strange life for Londoners in those days for even such simple things as going shopping or to church might mean one would never see one's home again — either it or oneself being blown to bits.

[Four Miles from Charing Cross, p. 313. She lived at no.25 Earlsfield Road.]

A little later she writes:

[Having] friends to tea in the flying-bomb season was a hazardous experience, for we often had to make a hurried exit into the passage by the kitchen, or the cupboard under the stairs, while one of them made its horrible sinister progress above the house, suddenly cutting out.

Time seemed to stand still as we waited for the sickening explosion, then rushed out of the house to see in what direction the dreadful, mushroom-shaped pillar of smoke would arise, symbol of the death and destruction beneath . . .

My brave little cat, Whiskers, a half-Persian tabby, took it all in his stride. Only on nights when the gunfire was very heavy did I bring him in his basket from the kitchen and put him beside my mattress on the drawing-room floor. He usually spent part of the rest of the night walking up and down my spine, possibly to assure himself I was still there. I was very much there.

Irene Caudwell's memoir is a gold-mine of local experience and observation from the end of the nineteenth century to after World War Two. It absolutely must be transcribed and published.

I notice that St Anne's Church (which I mentioned a number of times last month in association with Wandsworth's great sewer-aqueduct) is currently celebrating the 200th anniversary of its consecration in 1824. In the nineteenth century, some of its most prominent members, such as James DuBuisson and its sometime curate, Revd John Conder (later Head of Halbrake School), were stalwarts of the fight to save Wandsworth Common.

Irene Caudwell was deeply involved with this church. Here is one of several passages in her memoir in which she describes St Anne's during and shortly after the war.

But this is not how St Anne's looked during the war. Irene Caudwell again:

St. Anne's received the blast from many bombs, gradually losing every window but one. The climax came with a second flying bomb close by when one of the great girders across the nave cracked and hung in a "V" shape over the centre of the church. We were classed as a "dangerous structure" but all the services were carried on as usual in the aisles, which fortunately terminate in two chapels.

It was often a crush in spite of the evacuation of a large number of the congregation, often stone-cold, very draughty and extremely dark. Noisy too, for even a slight breeze set all the first-aid blackout in the glassless windows flapping and shaking.

Two of the people killed by that second flying bomb near the church were pathetic old ladies, who had a premonition that this would be their end, so that at the sound of a siren they always hurried to the house of a friend nearly opposite. This time they did not have time to leave their home.

Nor did they ever leave it, until their poor little broken, lifeless bodies were reverently lifted from the ruins. A few days later they had a double funeral in the Lady Chapel of St. Anne's.

[pp.314-15]

I wondered who these these two "pathetic old ladies" might be. I turned to the Commonwealth Graves Commission listings for Wandsworth and found that they are Caroline and Matilda Newton, of 24 Rosehill Road, who died on 3 July 1944. They can be seen among the seven people who died nearby on that day:

Let us return to examples of houses built on bomb-sites, this time caused by V-weapons.

As we saw in April 2024's Chronicles, a section of terraced houses (built around 1900 on the site of the Bevington family's Ivy House) was eventually replaced by Alexander Court, on West Side (facing the Common).

The Lyford Road bomb, 23 July 1944.

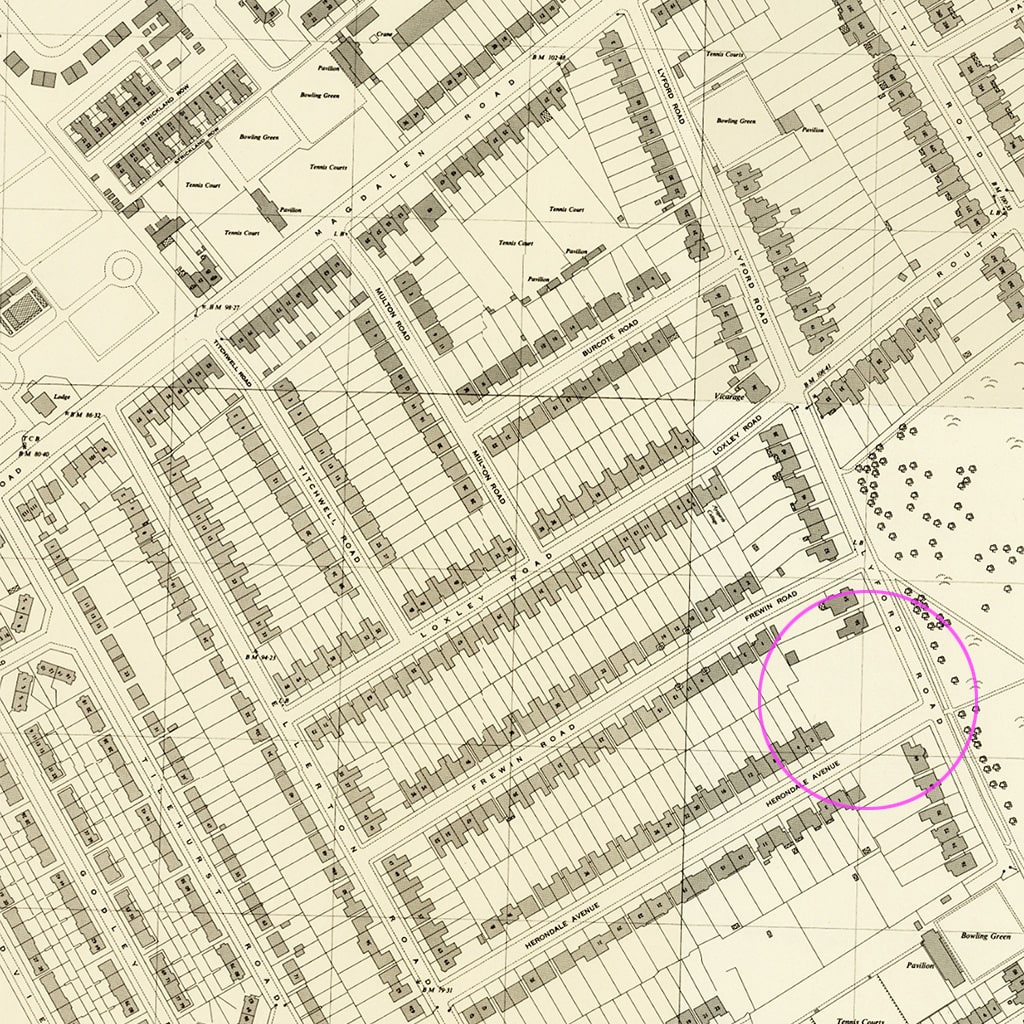

I would like to finish this Cook's tour of bomb locations with a look at the V-1 that annihilated a number of houses facing the Common on Lyford Road (and damaged many houses along Frewin Road), and another that landed nearby on the Scope (damaging houses on Routh Road and Trinity Road):

Avril Crossland (who still lives nearby) recalls playing on the massive hole left by the V-1:

"As a youngster (I must have been 9 or 10 at the time, so 1954 or 1955), living in Frewin Road, one of my favourite activities on the Common involved the bomb crater.

It was on the Scope near my road and near the edge of the Common.

The steep (as it seemed to me) sides of the crater were perfect for slithering down into the pit on our bottoms.

My friends and I felt most adventurous (no bikes) as we hit the bottom of the crater then clambered up again to repeat the thrills again and again.

I remember seeing the crater still there in the late 50's.

I also remember another crater on the Scope edging onto Trinity Road that was also enjoyed by all."

[Personal communication, September 2024 — thanks, Avril!]

[I wonder what the dimensions of Avril's craters' were? Today, there's no evidence (that I can see) of the Lyford Road crater. But what about the Scope? Is it the patch of protected Molinia grass? How was the hole filled in?]

[On the relationship between the size of bombs and the craters they cause, see e.g. Pillbox.org: Bomb craters (1) and Bomb craters (2).The authors remark that the craters were often more saucer-shaped than the "V" in the diagram.

According to the sources cited, a 200lb (100kg) bomb might create a crater up to 30 ft (9m) across, and 10 feet (3m) deep. A crater made by a 1000lb (500kg) bomb might be up to 50 feet (12m) across and 16 feet (5m) deep. The craters often filled with water very quickly.

Another source states that the impact craters of V-2 were up to 80 feet (24 m) across and of a similar depth which filled with debris to a depth of about 35 feet (11 m).]

The bombed houses were cleared and the plot left open for some years (which is why Avril and young friends could play on it so memorably):

What was built on the site of the Lyford V-1?

This is a view of the house on the corner of Lyford Road and Herondale Road today (2024) — no.64:

No, not this house. Here is the same view a decade or so earlier, in 2012:

So what happened?

Clearly, the original Edwardian house on the corner that was destroyed in 1944 and replaced around 1950 in a "similar but different" style was itself demolished in the 2010s and a rather larger one erected in its place.

[Given that Lyford Road is in a conservation area, I imagine the developers of the house on the corner (now 64 Lyford Road, though the front door is now round the corner on Herdondale Road) argued that the 1950s replacement could itself quite legitimately be replaced.

And so it might go on?

Lyford Road's cluster of "similar-but-different" post-war houses

Thanks to the V-1 bomb that landed here in July 1944, Lyford houses 58—62, and the corner house 64 Herondale are not typical of others in the road. They're certainly not identical to those they replaced, but they are quite similar — similar enough (I imagine) for most passers-by not to register the differences.

Have a look at these adjacent houses:But even the Lyford/Herondale corner house that we viewed above visually rhymes with the original whose replacement it replaces (sort of).

Eight people killed . . .

Eight people were killed, four houses demolished, and twenty more severely damaged. So far I've discovered very little about the people who lived and died in the houses, but I'm working on it. Here's what I've gathered from the CWG casualty reports for the V-1 that struck on 23 July 1944, and other sources:

At 60 Lyford Road:

Agnes O'Gorman, 45, wife of Colin O'Gorman.

Stella Stafford-Clarke, 2, wife of Carrol Stafford-Clarke (H.M. Forces).

John Taylor, 17, son of the late William Taylor.

At 62 Lyford Road:

Creina Muriel Margaret McFarlane, 38, daughter of Malcolm Stewart McFarlane and Norah Jane McFarlane.

Malcolm Stewart McFarlane, 64, son of the late George McMurray McFarlane and Margaret Ann Stewart McFarlane; husband of Norah Jane McFarlane.

Norah Jane McFarlane, 65, wife of Malcolm Stewart McFarlane. Died at 62 Lyford Road.

At 64 Lyford Road:

Clara Gertrude Dixon, 77, widow of John Fitzmaurice Dixon.

Cecil Claude Dixon, 50, Lieutenant, Home Guard, son of Clara Gertrude Dixon, and of the late John Fitzmaurice Dixon, husband of Maie Victoria Dixon.

Heavy Rescue Service: awards to two A.R.P. men for brave conduct when a flying bomb struck houses in Lyford Road . . .

The official citation states that "A flying bomb demolished a house and a casualty was trapped under the wreckage close to a wall. Leader [Frank Osborne] Mitchell worked into the debris, cutting around a settee which was holding up fallen timbers, and formed a tunnel 12 feet long. Owing to the confined apace it was impossible to strut the tunnel and all debris had to be passed back.

During the work the N.F.S. [National Fire Service] dealt with an outbreak of fire over the centre of operations, while the party wall above was in such a precarious condition that a man had to be stationed to give warning of movement.

On the arrival of relief, Mitchell asked to be allowed to complete the rescue as he knew the state of the tunnel. He eventually extricated the casualty alive after approximately four hours continuous work in dangerous conditions.

Mitchell showed courage and devotion to duty and a complete disregard of his own safety.

Frank Mitchell was awarded a B.E.M.[British Empire Medal], and his co-worker Harry Gustav Molin an official commendation for bravery.

I was largely inspired to focus this month's Chronicles on V-weapons in our area when I heard that Cathy Rowntree would be giving a talk to/for the Friends of Wandsworth Common in July on the V-1 that struck near Honeywell School on 23 June 1944. You can see a wonderful video of Cathy's talk, made by John Crossland, here:

HONEYWELL EVACUEES AND THE V1 BOMB

07/24 — Watch this fascinating curation of personal stories from former pupils of Honeywell school, related by Honeywell archivist and long-time local resident Cathy Rowntree. Honeywell school is on the edge of Wandsworth Common and was recalled fondly by many of the interviewees in our oral history film ‘Common Memories’. Lots of artefacts too, including a real WW2 gas mask!

Another encouragement was Geoff Simmons, whose recent walks (mainly along and around Garratt Lane) have been about the "Doodlebug Summer" 80 years ago:

On Sunday November 17 2024 Geoff will be leading a walk to remember one of the most significant WW2 bomb incidents in Wandsworth and the 34 people who lost their lives at Hazlehurst Road, Tooting, that day in 1944.

I went on one of Geoff's walks in late August and loved it. Incredibly stimulating. Thanks, Geoff!

— Summerstown 182 [Geoff's website]: November 19th 1944

— London Remembers: Hazelhurst Road WW2 bomb

— A London Inheritance: Launch and landing sites of the first V-2 on London

I must mention Robert Harris's novel, V-2 (2021). Some might say it's not so much a novel as a lightly-fictionalised precis of the early history of rocket missiles. But very readable all the same. Includes vivid descriptions of the effects of aerial bombardment.

Finally, in addition to Avril Crossland and Stephen Henden (thanked above), I would like to express my gratitude to Trevor and Hugh Betterton, who grew up on West Side, for corresponding with me about their recollections of the war and its aftermath in our area.

Highly recommended . . .

[See also the War Comes Home Facebook group ("War Comes Home honours Battersea's civilian experience in World War II with a varied programme carried out local residents". I'm rather embarrassed to say I knew nothing of this project until now. I'm not sure whether the group continues but I would very much like to learn more.]

Back in June, Graham Jackson emailed to remind me that September would be 100 years since the South African Cricket Team played on Trinity Fields:

We are approaching a notable sporting centenary (if you include Trinity Fields as part of Wandsworth Common) — 17 September 2024 marks a hundred years since a visit by the South African cricket tourists to Trinity Fields for a charity match on their way from Scarborough to catch the boat home from Southampton.

Most of the information regarding this match, including the scorecard, was recorded in the Wandsworth Borough News at the time and the event is included in my book A History of Trinity Fields (pp.76-77, scorecard on p.191).

You will not find this match in their official itinerary but it was obviously added on after the match at Scarborough and marked the very last cricket match held under the auspices of the Heathfield club before they moved to their current premises in Lyford Road (where it remains today solely as a bowls club) . . .

The choice of the beneficiaries for this game were interesting. Bolingbroke Hospital was one, but the others were connected with the licensed drinks trade, namely the Licensed Victuallers’ School and their Benevolent Institution.

As I've commented before, Graham has written a wonderful history about what is now called Trinity Fields — lots about sport, of course, but much much more. Here is an extract:

About 2,000 people were there to witness the match, and although the London Clubs batted first, and dismissed at lunchtime for 161, this would seem to have been a reasonably satisfactory, but inadequate, score, considering the quality of the opposition.

The players were entertained at the Surrey Tavern who were no doubt also supporting the match. Afterwards, perhaps having received too much ‘lunch’, the South Africans were bowled out for a meagre 55 — to lose by 106 runs! They only batted ten, as M.J. Susskind was listed as “Absent” but was this because he was injured during fielding, or simply did not turn up for the match, or spent too much time enjoying an extended lunch interval in the Surrey Tavern? We do not know.

Although this was in effect an exhibition match, it was nevertheless, a victory very much against the odds which members of the London Clubs team could relate to future generations as ‘The day we beat the South African Tourists’ . . .

[I]t is not known precisely why the Field was selected for such a match. Maybe it was intended as a swansong because it was known that the Heathfield Club was closing as a cricket club after fifty years, or possibly because in the past both George Lohmann (as assistant coach to the South Africans Tourists in 1901) and Charles Mills (the ex-Heathfield club player, who had toured with the 1894 South Africans) had strong connections not only with the Field but also with the tourists.

In any event, it would have been a fine ‘send-off’ for club cricket at the Field and certainly of local interest as witnessed by the attendance.

Poignantly, however, this match, would have been the last time that the Heathfield club would have a connection with cricket, and their indigo, blue and white flag (they would certainly have had one) which fluttered above the pavilion for perhaps almost forty years, would be lowered for the final time.

You may remember George Lohmann — one of the greatest bowlers of all time — from August 2022's Chronicles:

"All his early practice was had on Wandsworth Common, and, in fact, the whole of his cricket until he was fifteen or sixteen years of age was learned on the Common . . . "

If you would like a copy, email Graham at graham.jackson@btinternet.com.

Oh dear, I think perhaps I'm developing a bit of an obsession with the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum/Building.

On Armistice Day, Tuesday 11 November, I hope to give a talk to/for the Friends of Wandsworth Common on the 3rd London General Hospital. The venue as usual will be Naturescope, on the Common. Let me know if you want more info.

Here's a little video I made a few years ago:

And eventually, if given the chance, I'd like to talk about "The Short Life and Hard Times of Charlotte Bennett: The 'ghost' in the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum".

Charlotte really should not be reduced to a spooky presence. She was a real person worth knowing more about. And there's a lot to be said about the setting up of the RVPA after the Crimean war in the 1850s (on 50 or so acres of Wandsworth Common), its chaotic and controversial early years when it stumbled from one scandal to another, and of course about the lives of the first orphaned girls to be sent there.

One of my very favourite writers on the Open Spaces Movement of the C19, Elizabeth Baigent, is to give a talk on "Octavia Hill and Wandsworth" to the Wandsworth Historical Society on Friday 27 September.

Info. provided by Pamela Greenwood, WHS — thanks, Pamela!

WHS Monthly Meeting Friday 27th September 8 pm at the Friends Meeting House, Wandsworth High Street

‘Octavia Hill and Wandsworth: how her work in the Wandsworth area sheds lights on her wider reforms’, by Elizabeth Baigent.

Octavia Hill (1838-1912) was one of the nineteenth century's most influential social reformers, with a particular concern for the welfare of the urban working class. She promoted social housing and the preservation of open spaces in cities. She was one of the three founders of the National Trust.

Elizabeth Baigent began her work on Octavia Hill while she was Research Director of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. She later organised a University of Oxford/National Trust conference on Hill to mark the centenary of her death. She continues her work on early conservationists as the University of Oxford Reader in the History of Geography.

We welcome guests - our meetings are free. No need to book - just come along. We look forward to seeing you there!

Tea and coffee will be served after the talk.

The Friends Meeting House at 59 Wandsworth High Street, SW18 2PT, is easily reached from Wandsworth Town Station, and by a number of bus routes with nearby stops, for example, 170, 87, 39, 37, 337, 485, 44, 156, 220 and 270.

— Wikipedia: Octavia Hill

— Wikipedia: Robert Hunter [along with Octavia Hill and Hardwick Rawnsley, Battersea-resident Robert Hunter was one of the three founders of the National Trust]

— Wikipedia: National Trust

In the latest issue of the Wandsworth Historian we recall the many achievements of the Battersea-based sculptors Horace and Paul Raphael Montford, find out how to explore the records of the Wandsworth & Clapham Union Workhouse, and uncover even more details about Queen Mary’s fateful car crash in Wimbledon Park Road in 1939.

We also take a glance at how a Balham builder advertised his wares in Edwardian times, and look back at the early days of the Roehampton-based Hare & Hounds Club of cross-country runners which still flourishes today.

All this and more in the Autumn 2024 issue of the Wandsworth Historian (ISSN 1751-9225), the magazine that brings you the latest research into Wandsworth’s past.

The Wandsworth Historian is published by the Wandsworth Historical Society, and copies are available price £3.00 plus £3.00 for postage and packing from WHS, 119 Heythorp Street, London SW18 5BT or by emailing neil119@gmail.com. Cheques payable to ‘Wandsworth Historical Society’, please, though on-line payment is much preferred.

The website address of the Wandsworth Historical Society is www.wandworthhistory.org.uk.

Neil Robson

16 September 2024

I'm very much looking forward to receiving my copy. I'll read every last word (I always do), but the Hare and Hounds article sounds particularly enticing (since the runners, having set off from Roehampton, sometimes crossed Wandsworth Common and the Surrey Pauper Lunatic Asylum grounds).

Here are a couple of images from the 2022 talk:

I'm very happy to hear that the indefatigable Jeanne Rathbone has achieved more public recognition for Battersea residents Laura Barker and Tom Taylor.

More news from Pamela Greenwood:

Battersea Society Blue Plaques, Saturday 28th September

Battersea Society plaque unveiling on Saturday 28th September at 2 pm to Tom Taylor, playwright, and Laura Barker, composer, on 84 Lavender Sweep SW11 on the site of Lavender Sweep House. It was visited by eminent Victorians at their Sunday soirées. Tom wrote Our American Cousin — the play Lincoln was watching when assassinated. Unveiling by Lord Fred Ponsonby and actor Alun Armstrong with music and readings.

Tom Taylor — long-time contributor to Punch magazine and a great defender of Wandsworth Common in the C19 — has been mentioned a number of times in these Chronicles.

For example, you may recall his fine poem The Warning of Wandsworth Common (1865) that begins:

MIDNIGHT lay still on fair West Hill,

Wandsworth snored silent nigh;

But for yell and scream of the whistling steam,

As the darkling trains roared by.

That sound alway, both night and day,

Must Clapham Junction hear,

Now Battersea Plains are a place of trains

That 'sparagus erst did rear.

See the entire poem here. Stirring stuff.

Talk by Sue Demont on the history of Bolingbroke Hospital, a pioneering healthcare facility on the edge of the Common.

A HARLEY STREET FOR THE POOR?

The Lives & Times of Bolingbroke Hospital

a talk by Sue Demont

Tues Sep 24th, 6.30 for 7pm, Naturescope

The Bolingbroke Hospital bordering Wandsworth Common provided a comprehensive array of medical services to residents across Battersea and Wandsworth until it closed in 2008. Its open air ward and famous nursery rhyme frieze in the children's ward are particularly noteworthy. Sue Demont explores the hospital’s architecture and operation over 128 years, including the contributions of some illustrious patrons.

At the Naturescope, Wandsworth Common, Tuesday 24 September 2024, 6:30 for 7pm. You can book a place using this link.

SO many more stories still to tell. But that's all for now, folks.

If you would like to receive occasional notifications of new Chronicles, let me know.

This search box is not very consistent, but always worth a try:

Send me an email if you enjoyed this post, or want to comment on something you've seen or read on the site, or would like to know more —or just want to be kept in touch.

September 2024

Return to the top of this page . . .