I suppose you could say I owe my existence to war — wars in the Aegean, Anatolia and the Caucasus, in Palestine, in North Africa, and throughout Europe.

My mother, Lemonia Asnay, was born in Alexandria, Egypt. She was ethnically Greek. Her parents, born in the 1880s in the Ottoman empire, had made their way to Egypt as teenagers, separately and alone, from Smyrna (Izmir) and the mountainous Aegean island of Ikaria. My grandmother was fleeing poverty, my grandfather conscription in the Ottoman army (in effect, a death sentence for ethnic Greeks).

My father, Edward James Boys, was a prison officer, a farmer's son from Sussex. He was athletic — a keen racing cyclist — and adventurous. They had met before the war after he volunteered to serve with the Coldstream Guards in Mandate Palestine. He had landed at Alexandria, and mostly returned there between tours of duty for "rest and recreation". This involved visiting the sites . . .

Seeing the sites, and seeing as much as possible of my mother:

Once World War Two started, my father spent long periods in the North African Desert. My parents couldn't see one another very often, and in 1941 he was captured at Tobruk, so they were separated for the next five years. He spent several years as a prisoner of war (or as an escapee on the run) in Italy and Germany. In short, by 1945 he was no stranger to confinement.

It took a while for him to recover from malnutrition and jaundice, and perhaps other things too, but eventually he wrote to my mother, asking her to come to England to marry him. And she agreed. (Without doubt the worst decision she ever made, she always said.)

She travelled (alone) to London in 1947 just in time to face the worst winter anyone could remember. Given her paradisal pre-war life in Alexandria, it must felt like she had been expelled from Eden.

I imagine my father felt very differently about the experience. For him, the main thing was that he was still alive (unlike most of the men he had joined up with), and anything was better than Stalag IV-B. He had survived his season in Hell.

With difficulty, my parents found a flat to rent for a while in Pimlico; but if they were to have a child (i.e. me) they needed a more permanent home; and that is why my father joined the prison service and was sent to Wandsworth.

Liberated through one gate, he had chosen to enter another. But at least it was one he could escape through every single day.

[Heathfield Avenue: for more than a century a broad avenue of (lime) trees stretched out from the prison gates, and led to Trinity Road and Wandsworth Common. Inside v. Outside. Dark v. Light. Captivity v. Liberty. When Trinity Road was "dualled" in the late 1960s, the Avenue was cut short, and all that engineered symbolic power was lost.]

All four of the homes we shared were practically in sight of one another, and it was never more than a couple of hundred yards from one to the next.

So, after all their trans- and inter-continental travels, my parents rooted themselves permanently in Wandsworth. In 2002, after 54 years in the area, they died within a few weeks of each other. Their last home was on Trinity Road.

These are the homes in which I lived for the first twenty years of my life. And after various spells away (including twenty years as far away as Calbourne Road in Balham) in 2004 I moved to Loxley Road, which is where I live now.

Here is a slightly wider view of the same area today:

Not very much. Perhaps the strangest thing to notice is how similar the two scenes are. They were photographed seventy-five years apart but you will have to look twice to see any differences between then and now. There can't be many parts of London that have been less altered.

[Compare the stability of the Common and its surrounding streets with, for example, the radically transformed Thames-side Wandsworth and Battersea — where factories, gas works, power stations and Victorian housing (some but not all of which were slums) have been swept away to make space for "luxury apartments", office blocks, and the Thames Path. This process continues at pace, of course, but not generally around the Common.]

Let's have a look at some of the remaining physical signs of the recent war, which had ended only four years earlier. I'll start with bombs and bomb-sites.

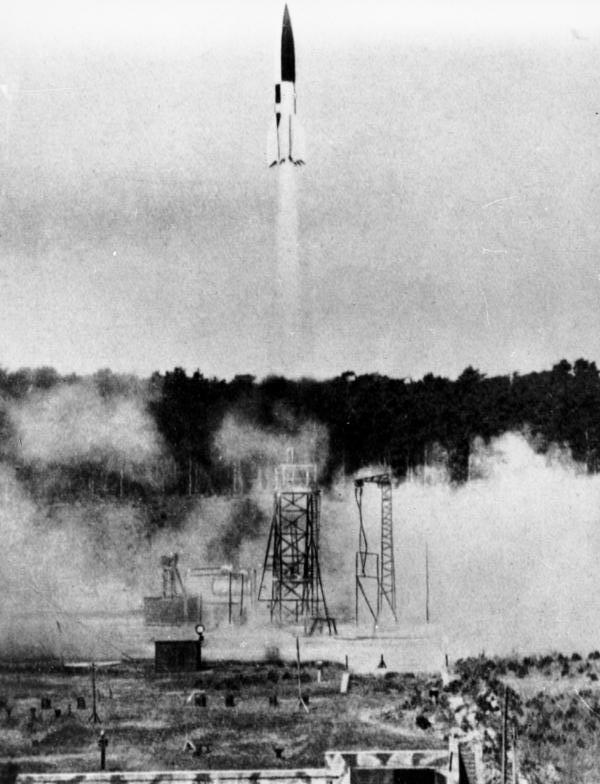

I don't know how many buildings were destroyed or damaged in Battersea and Wandsworth but Jim Slade has estimated that about 2,729 high explosive bombs and mines, 160 V1 flying bombs, 8 V2 rockets, and roughly 50,000 incendiaries were dropped here. Around 1800 people were killed and 8,900 injured as a result.

[See Jim Slade, "WWII Air Raid Casualties in Battersea and Wandsworth", Wandsworth Historian no.82, 2006.]

The meticulous LCC bomb damage maps show an almost random spread of destruction:

Black — Total destruction

Purple — Damage beyond repair

Dark Red — Seriously damaged, doubtful if repairable

Light Red — Seriously damaged, repairable at cost

Orange — General blast damage, minor in nature

Yellow — Blast damage, minor in nature

Green — Clearance areas

Small circle — V2 Rocket

Large circle — V1 Flying bomb

It's worth checking where the bombs fell, and match the locations with what has been built on the site.

Here's an example of the destruction caused by a V-1 Flying Bomb on West Side. The row of houses that were destroyed had been built around 1900 on the site of the Bevington family's Ivy House:

And here's Alexander Court, the block of flats built on the site of the V-1 flying bomb explosion. Any idea of the date of construction, anyone?

[Hugh Betterton, 29 March 2024: "I believe that Alexander Court was built in the 1950s, as I had a couple of friends who lived there and I played with them when I was still at Swaffield Primary school (mid/later '50s). I can't recall flats being built though. "]

Smaller (and less numerous) circles represent V-2 rockets. These fell in the period 8 September 1944 to 6 March 1945.

I'll return to the V-2 after a short intermission.

Seeing these wonderful cutaway images of the V-1 and V-2 reminded me of the Eagle comic . . .

Well, not quite. But there is a connection . . .

Although its first edition did not appear until 1950, Eagle comic was conceived and developed in 1949 in part by the Revd Chad Varah, a young vicar at St Paul's Church on St John's Hill.

Chad Varah described himself as the "Scientific and Astronautical Consultant" to Eagle, supporting the superb artist Frank Hampson and working closely with his friend the publisher Marcus Morris (himself also a vicar). Varah wrote many of the stories that appeared in the Eagle, and also in other comics that appeared at this time, including those with a mainly female readership such as Girl (1951), Robin (1953) and Swift (1954).

Chad Varah and Marcus Morris were attracted to comics as a means of promoting the work of the church to the young (it seems they had more or less given up on the old) and combating what they saw as the pernicious influence of US comics. (Morris described them as "deplorable, nastily over-violent and obscene, often with undue emphasis on the supernatural and magical as a way of solving problems".)

Their initial idea for an all-British comic-strip superhero was Lex Christian, "a tough, fighting parson in the slums of the East End of London". But they soon saw sense and Dan Dare was born. At its height the Eagle comic sold more than a million copies a week.

[Wikipedia: British comics, and Eagle (British comics).]

But this is not all that was gestating on the edge of Wandsworth Common in 1949. Chad Varah was also developing an idea for an emergency telephone service to help people who were contemplating suicide and had nowhere to turn — Samaritans.

["Varah began to understand the problems facing the suicidal when he was taking a funeral as an assistant curate in 1935, his first church service, for a fourteen-year-old girl who had taken her own life because she had begun to menstruate and feared that she had a sexually transmitted disease."]

The Samaritans launched a few years later, in 1953, after Varah had moved from Wandsworth to a City church where he had more time to devote to the project.

See also Wikipedia Samaritans (charity).]

[Peter Farrow emailed to wish me happy birthday - thanks, Peter! - and to say he believed he had been baptised at St Paul's by the Revd Varah.]

[PB, 6 April 2024: Since writing about Chad Varah and Dan Dare last week, I've discovered that two short articles about him were published in the Wandsworth Historian (WH 93 Spring 2012, and WH 94 Autumn 2012). The first featured a monochrome image from "The Red Moon Mystery". Here it is again, now in glorious in colour.]

While the chief pilot of the Interplanet Space Fleet, Dan Dare, is on a skiing holiday in North Mars with his loyal batman, Albert Digby, he is requested by his controller to investigate a mysterious asteroid nicknamed the Red Moon which is ominously heading towards Earth.

Dare makes for a nearby satellite space station where he finds that a full-scale evacuation of Mars is already under way. Hence the remark appearing here out of Digby’s mouth as they attempt to manoeuvre their ship through the other spacecraft: "Gosh, Sir – it’s like Clapham Junction," that locale being a metaphor for traffic congestion.

By 1949, some of the bomb sites had been cleared, but little rebuilding had taken place. Many continued to function as informal playgrounds for children, offering limitless opportunities for creative (and destructive) play. They certainly did for me.

One of the bomb-sites we played on as children is at 9 o'clock. I recall someone had painted "42a Looksee Villas" on one of the piles. Why has this stuck with me? ]

The longer the site remained undeveloped, the more it filled with "Fireweed" (Rosebay Willowherb aka "Bombweed"), Ragwort, Buddleia ("Bombsite plant", "Butterfly bush"), and Brambles.

[Incidentally, Marjory Allen (nee Gill, later Baroness Allen of Hurtwood) was inspired by seeing children hard at play on these bombsites to create numerous "adventure playgrounds". One is sited on the Common near Chivalry Road, where it provides adventurous play for children with disabilities living in the Borough of Wandsworth.

You can learn more from Sue Demont's talk for the Wandsworth Heritage Festival, "An uneducated lady? Marjory Allen and the Adventure Playground Movement" (31 May 2023) — the video's available on the Friends of Wandsworth Common's website, or YouTube.]

Having lived for a decade in small Victorian flats in the shadow of the prison, my parents were thrilled to move into a brand new "maisonette" (a living room and small kitchen downstairs, three bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs).

[I spent my last few months at Beatrix Potter School here (it was then infants-only), I moved aged 8 to Tranmere Road (Earlsfield) Junior School, and on to Emanuel at 11. It was from this home that I started at university, but by the time I'd graduated my father had retired and my parents had moved to Chesham Court, on Trinity Road (on the edge of the circle, at 2 o'clock).]

Let's look briefly at the allotments, still much in evidence over nearly half the Common in 1949. (Food was of course still scarce in 1949, expensive, and rationed, so many people chose to continue "growing their own"). But it was only a matter of months before the Common would be restored, principally to make way for sports.

You can see the extent of the allotments clearly on this 1947 view:

There are SO many more signs of the war in this image, but one of my favourites — and it's still visible today — is the railway bridge on Heathfield Road. Notice the white stripes, presumably painted to help drivers during blackouts.

Since it's my birthday, and since I can safely assume that nobody is still reading this far down the page (if indeed anyone ever started), I'll indulge myself with yet another photograph of me me me with my parents. It was taken on Wandsworth Common in 1949.

I hope you've enjoyed this month's Time-Traveller's Tour of Wandsworth Common. I think I'll probably continue the 1949 story next month because I've had to pass over some quite big stories — for example, what people were watching at the Granada cinema, Clapham Junction, what happened to the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building, and to local education, and the imminent (and appalling) fate of Trinity Road). Let's see.

SO many more stories still to tell. But that's all for now, folks.

If you would like to receive occasional notifications of new Chronicles, let me know.

This search box is not very consistent, but always worth a try:

Send me an email if you enjoyed this post, or want to comment on something you've seen or read on the site, or would like to know more —or just want to be kept in touch.

April 2024

Return to the top of this page . . .