The super-sewer that crosses Wandsworth Common

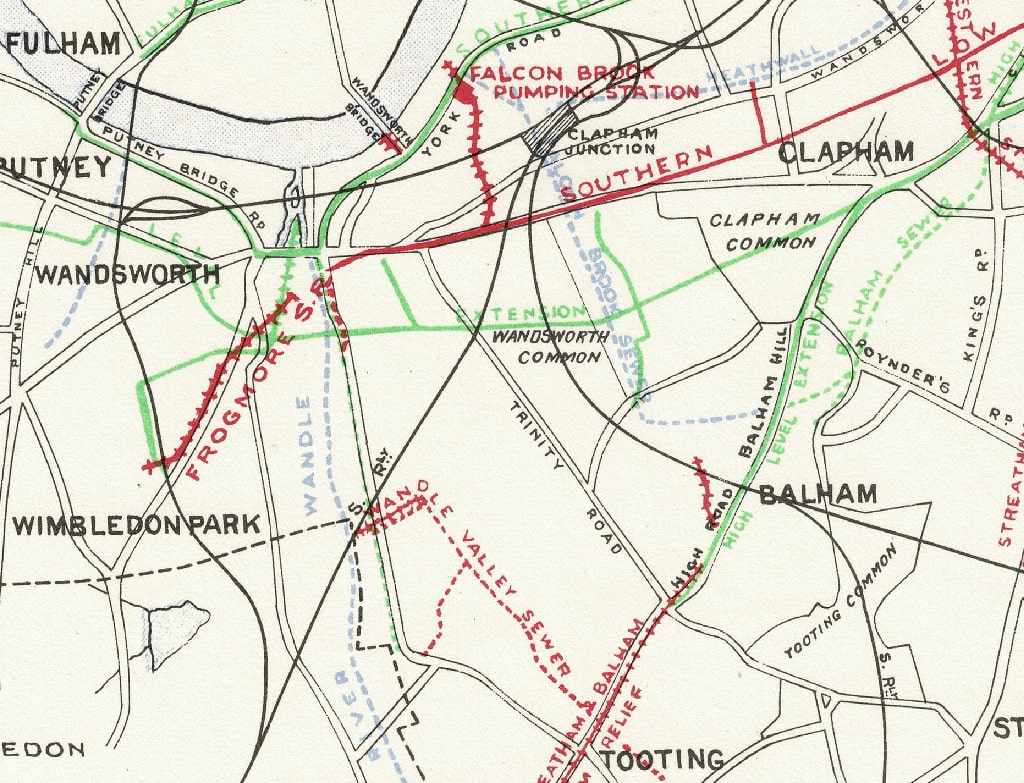

No, I'm not going to claim that a giant aqueduct once bestrode the Common. But, perhaps surprisingly, they were connected. Here's a diagrammatic map from an article by the "Sewer King" Joseph Bazalgette in 1886 showing the course of a new main sewer from Putney to Clapham:

For some reason, Bazalgette describes the sequence from right to left, against the flow:

Commencing at the Bedford Arms, Clapham, the sewer passes along High-street, Clapham, across Clapham Common, Wandsworth Common, St Anne's Hill, South-street [i.e. Garratt Lane], Wandsworth, the river Wandle, the Merton-road, along nearly the whole length of Ringford-road, along the Upper Richmond-road across Putney-hill, Putney Park-lane, and grounds, to Roehampton later.

But where exactly was/is the sewer? This is the main theme of August's Chronicles.

When I was young (in the middle of the last century), school holidays were always hot and dry — every August day was a scorcher. It really was (at least, that's how I recall it). So what were we to do? Earlier generations might have cooled off in one of the ponds on the Common, but we were much too fearful of "Parkies" (the brown-suited, trilby-hatted, bicycle-riding keepers who kept an eagle eye on everything).

So, as often as we could afford it, we went to the open-air swimming pool in King George's Park, just the other side of the Wandle.

Although we were still juniors — 9, 10, 11 years old — we enjoyed more or less complete freedom. In the benign absence of parental control, we travelled all over London, in groups or indeed alone.

Our route from the Prison Quarters lay along Heathfield Road and down the oddly named Allfarthing Lane (another puzzle for you), threaded its way through the Wendelsworth estate (note the archaic form of "Wandsworth" in what was then a modern housing estate still in construction), crossed the Wandle, and arrived at the Lido. We often had to wait in a long queue to go through the turnstile, but it was worth it.

[Incidentally, we nearly always stopped on the way to the pool in a row of shops opposite Allfarthing School to buy a pomegranate to eat, or a bunch of liquorice root sticks to chew on. Occasionally, we boys stopped to have a barber cut our hair. He sat us on a board to raise our heads to a better height. Most of the shops have been converted into houses now, only the corner cafe remains (for years this has been called "Mehmet's", but it was something else then. I seem to recall it was a steamy place, much loved by Teddy Boys, or were they proto-Rockers?). ]

[For some lovely recollections of King George's Park Lido, with interesting details, see e.g. Facebook: Wandsworth and Battersea memories live on: Who remembers the Lido in King George’s Park? The thread starts with a question from Emma Coldgun in 2021:

"Who remembers the Lido in King George’s Park? Wandsworth Open Air Pool was built in 1938 , became The Big Splash in the 1980s but sadly it went the way of many open air swimming pools, closing in 1993."

See also:

— Baths and Wash Houses Historical Archive: Wandsworth Swimming Facilities.]

— Wendelsworth Residents Association: History of Wendelsworth Estate

— Municipal Dreams in Housing: A Brief History of Council Housing in Wandsworth, Part II: 1945 to the present.]

Although we didn't know it at the time, we were treading in the footsteps of literary giants.

In the 1880s, the poet Edward Thomas (born 1878) often took a similar route to the Wandle and beyond. He crossed the Common from his home on Wakehurst Road and headed for Allfarthing Lane:

"Allfarthing Lane was worth going down for its name's sake. We invented explanations and repeated those of our parents. At the top dwelt an old woman in what looked a one-room hut who presumably knew and had something to do with the origin of the queer name. But above all, whichever way we took, the Wandel had to be crossed.

Going by Wimbledon we had to cross the bridge by the copper mill. You might stop to look down at the fish or along at the fishermen, or to carve your name on the parapet.

In Wandsworth there were two bridges, fishermen hanging over the less frequented one who were never seen catching anything but never exhausted our curiosity.

But best of all was the middle way through Earlsfield, crossing the Wandel at the paper mills. The smell of the mills wafted over a mile and a half on certain still evenings gave me a quiet sort of poetic delight. Hereby the water ran over a steep artificial slant, swift, glittering, and sounding; and sometimes we stayed here and caught minnows instead of going on to Wimbledon.

It was the first place where I saw and realised the beauty of bright running water. We paddled with our stockings in our shoes and our socks tied together and slung over our shoulders. We talked and laughed and shouted and splashed the water.

I cannot remember cold or rain or any clouds there.

[From chapter 2 of Thomas's marvellous The Childhood of Edward Thomas: A Fragment of Autobiography (first published in 1938 but written before WWI). This was well before the creation of St George's Park or the swimming pool in the first third of the twentieth century, but not of the aqueduct, which must have been in construction or recently finished — but which he never mentions.]

[Notice, by the way, that Edward Thomas always spells it "Wandel". Until recently, I assumed this was in deference to his idol Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler (1653), But contrary to received opinion, Walton never once mentions the river, in any spelling. (I spent hours scanning through every edition I could find.)

Sadly, the widely-repeated references to Walton describing trout “with marked spots like a tortoise”, said to be unique to the River Wandle, are a much-later editor's additions (they first appeared in the 1830s).

No, "Wandel" is how another of his heroes, John Ruskin, spells it —as in "The Springs of Wandel", a chapter in his elegy for lost people and places Praeterita. This was published in 1888, when Edward Thomas was ten, and clearly an inspiration for his own autobiography.

I must return sometime to Ruskin's contrast of the paradisal Wandel of childhood memory (with its "cress-set rivulets in which the sand danced and minnows darted") to the "same" place revisited in later life, where:

"the human wretches of the place cast their street and house foulness; heaps of dust and slime, and broken shreds of old metal, and rags of putrid clothes; which — they thus shed into the stream, to diffuse what venom of it will float and melt, far away, in all places where God meant those waters to bring joy and health."

[Preface to The Crown of Wild Olive (1866, 1873).]

Across King George's Park, within sight of the pool, ran an extraordinary structure that I now know as the Wandsworth Aqueduct. But back then we had absolutely no idea where it came from, or where it was heading, and probably never asked ourselves.

I was reminded of this recently on a walk near St Anne's Church. Recalling from maps that the mighty sewer appeared to stop just yards short of the church, I found myself wondering where on earth it could possibly have gone to next. So that's why I've spent the last month or so collecting images and trying to determine its route.

I looked around for detailed maps, originally with little success — I even emailed Thames Water (who seemed not to comprehend my request — they simply cut-and-pasted into their email guidance for people wanting to build extensions who need to know where the local sewers run).

But eventually I accumulated a number of photographs and several (admittedly rather sketchy) maps. Here is a selection.

Naturally, the aqueduct drew admiring attention from passing aeroplanes:

Here's a map again, to help you see how everything fits together:

Much of the water shown on this map has since been filled in, including the New Cut (left), the Swimming and Paddling Pools, and the great header Pond behind the Mill Dam (top centre). Wandsworth Stadium too has gone. The site of the Optical Component Works is now Sainsbury's.

[Wandsworth Stadium is not to be confused with nearby Wimbledon Stadium, on Plough Lane, which also held greyhound races (and other sports) — see March 2022's Chronicles.

According to the Greyhound Racing History website:

"[Wandsworth] stadium was constructed on an area of unused land south of the Wandsworth reservoir between Garratt Lane (formerly South Street) and Buckhold Road. Just to the south was King George's Park (a public nursery, tennis courts, bowls green, swimming and paddling pools).

This tranquil setting was unfortunately ruined by an unsightly storm relief sewage aqueduct that ran straight over and through the middle of it."

(However, this "tranquil setting" was not enough to calm all local passions: "In 1936 rival gangs fought a battle in front of thousands of witnesses and one man was murdered after being stabbed to death.")

See also:

Greyhound Racing History: Wandsworth Track

Greyhound Racing Times: Wandsworth

Wikipedia: Wandsworth Stadium

The last meeting was 4 June 1966, after which the stadium was demolished to make way for the Arndale Shopping Centre.]

Much of the area is now South Side Shopping Centre (formerly known as the Arndale Centre, which opened in 1971, it was rebranded South Side in 2004). The River Wandle now runs beneath it, in a culvert. (It's hard to believe that an entire river would be "disappeared" in this way today — but who knows?)

[You might like to view some videos and blogs about kayaking on the Wandle, including a rather scary journey beneath the South Side. Not for the faint-hearted.

Inflatable Kayaks and Packrafts: Wandle: An Urban Packrafting Nightmare ("We had a good look, then shot this underground weir and were spat out the other end, grinning and alive.")

Canoe London: Kayaking the River Wandle in South London

I was going to add something here about Battersea author Michael de Larrabeiti's use of sewers and the Wandle beneath South Side as locations in his terrifying novel-sequence The Borrible Trilogy, but of that another time.

By the 1940s, the aqueduct was already dangerously dilapidated, and it was demolished in the early 1960s.

Curiously, it was the intensity of the sun — that same sun that drove us to the Lido — that did the damage. As L.B. Escritt argued it in his article "Sewerage Design and Specification" (1947), "aqueducts should be constructed in straight lines", never curved:

particularly if built with materials that make no allowance for expansion or if the direction of the aqueduct is from east to west, otherwise expansion in the heat of the sun may cause movement.

An outstanding example of this fault is the Wandsworth Aqueduct constructed by the London County Council [actually, the Metropolitan Board of Works]. In this case the sewer is carried east and west across the Wandle Valley on a series of heavy brick piers and arches. The whole of the construction curves on plan towards the south.

When the sun shines on the brickwork it expands but, being unable to move at the ends, it pushes southwards. On cooling it does not quite return to its original position and thus there is a tendency for the main body of the centre of the aqueduct to creep southward, and this has had the effect of fracturing the piers severely.

[L.B. Escritt, "Sewerage Design and Specification", Contractors' Record and Municipal Engineering (1947), quoted in D. Ainsworth, "Wandsworth Aqueduct", Wandsworth Historian 86, p.14.]

Joseph Bazalgette did not include the Wandsworth sewer aqueduct among his initial "intercepting sewers".

These were created in the 1850s and 1860s to run more or less parallel to the Thames to stop raw sewage reaching the Thames by flowing from higher ground to north and south. Now largely confined to underground pipes, the effluent was carried by gravity beyond London's eastern margins, where massive pumping stations at Crossness (south) and Abbey Mills (north) could raise the (initially untreated) sewage high enough (9 to 12 metres) to be disgorged into the Thames.

South of the river, three major interceptor sewers were constructed:

The high-level sewer starts at Herne Hill, and heads eastward under Peckham and New Cross to a pumping station at Deptford.

The middle-level sewer starts on Balham Hill and runs under Clapham High Street, under Stockwell and Brixton, through Camberwell to Deptford.

The low-level sewer begins in Putney and runs through Battersea, Vauxhall, and under the Old Kent Road and Bermondsey to Deptford.

Over time, new sewers were built, and rivers such as the Wandle and the Falcon Brook integrated into the overall network. Among these later sewers was the Extension, carried across the Wandle Valley on an aqueduct. It seems that the original intention had been to run a road along the top (which would have been nice), though this never happened.

Here is a helpful diagram from 1955, which helped me to work out where the Wandsworth "Extension" sewer went after it reached St Anne's Church:

But the following map, from the 1930s, shed even more light on the course. It may look like a tangle, but stick with it.

Here's the bigger picture:

And here's a view closer to home:

The sewer was dug both by "open cutting" (aka "cut-and-cover") and by tunnelling (the latter much more expensive). Most of the length used egg-shaped pipes, but some sections were circular. Their diameter varied from about 4" 6" to 7" (as in this cross-section).

The line I have drawn on the next map is conjectural, but based on the maps above. It would be good to have this confirmed using more detailed plans, but it is probably fairly close to the actualité:

As we have seen, the "Putney & Clapham Extension" sewer travels overhead across the Wandle valley to St Anne's Church within an aqueduct, at which point it goes underground. It then turns eastward to run in a straight line just north of the Trinity Road railway bridge, past the Patriotic Building, and beneath Wandsworth Common and the London to Brighton railway to a point near (and probably under) the Three Island Pond.

Having passed beneath Bolingbroke Grove, it turns down what was then called Chatham Road (the first part of which is now Cobham Close and Darley Road), and (across? beneath?) the Falcon Brook Sewer beneath Northcote Road.

The Extension then continues "between the Commons" to Clapham Common, and joins the Southern High High Level Extension at a point near Clapham Common Station.

The question arises of how such an immense sewer was laid across the Common, and with what results.

Alas, I have yet to find out very much about it at all. The newspapers of the day are oddly quiet about it. But here is an intriguing reference in a Conservators' report in March 1885:

The Metropolitan Board of Works having, under their general powers, constructed a storm-relief sewer passing under the common, with manhole shafts and entrances which are to remain there permanently, tho conservators took steps to secure, in aid of the Wandsworth Common rate, equitable pecuniary compensation. This will also serve to defray the cost of restoring the areas damaged during the progress of the work.

The conservators, further, obtained possession of about 4,000 loads of material, got out during tho progress of the sewer, which have been utilised in filling portions of the common which stagnant water has hitherto accumulated.

[BNA: Link.]

Understandably, the "4000 loads of material" were most welcome in the ongoing project to level, drain and re-turf the Common. These loads of earth and gravel have all simply vanished into the new flatworld thus created. But the "manhole shafts and entrances which are to remain there permanently"? Do they still exist? If so, where? And did the Conservators secure "equitable pecuniary compensation" to fund the restoration of the Common. How did Clapham Common fare?

I havent found out very much yet, but I'll add anything I come across.

Recent photographs of the Clapham Storm Relief Sewer and South Western Storm Sewer

Here are just a couple of examples, of many:

For more of these fabulous photographs taken in November 2020 by "urban explorers" with more guts than most, visit TwentyEightDaysLater: Clapham Storm Relief Sewer and South Western Storm Sewer.

— "Why did the aqueduct curve? Available land? Would look prettier from a balloon?"

— Did the Extension sewer go up and down like a flume? Surely it can't have had a regular, slightly falling gradient from west to east, given that Wandsworth and Clapham Commons are so much higher than the Wandle and the Falcon Brook, which are in valleys.

— If you dug down, could you find the sewer? How deep is it?

— Can you still walk along the section of sewer beneath the Common?

— What happened to all the rubble when the aqueduct was demolished?

— Do any signs remain of the aqueduct, and what has replaced it?

Send me your answers — and more questions, even if there's little hope of receiving any enlightenment.

For some reason all this talk of sewers reminded me of lavatories. So far as I know, no loos existed on the Common before WWI. And I have no photographs of them — for some reason, they never feature in postcards, the chief visual source we have for other features of the Common (such as the bridge and the lake, of which there are many).

A WANDSWORTH COMMON NEED

To the Editor.

Sir, Might I draw attention in your columns to the great need of public conveniences on the Common. Possibly some of the borough councillors might bring it to the notice of the L.C.C,, and put an end to the present state of affairs.

A LOCAL RESIDENT.

The rules and regs about "committing a nuisance", the euphemistic term, had always been clear. The Metropolitan Board of Works, when they took over management of the Common c.1887, asserted the following:

1. The Acts and things specified in the following Clauses numbered 1 to 23 respectively, of this Bye-law, are hereby prohibited —

6. Committing any nuisance on the Common, or against any of the trees, shrubs, walls, railings, or fences thereof.

This was carried over (and elaborated) when the London County Council replaced the MBW a year or so later, in 1889:

Committing Nuisances

26. Committing any nuisance in or on any park, garden or open space, or against any tree, shrub, wall, railing, fence, magazine, butt, mantlet, seat, or other thing, or under any arch, or in any pond, lake, or river. [p26]

[Butt: presumably a mound of earth (as in archery)

Mantlet: a portable wall, shelter or screen originally used in the middle ages for stopping projectiles.]

Misuse of Urinals, W.C.'s, &c.

29. Going or attempting to go into any water-closet, urinal, or other place of convenience provided for the opposite sex, or infringing any regulatious of the Council set up therein controlling the use thereof.

Conveniences.

64. Conveniences must be kept open from 9 a.m. until half-an-hour after sunset. They must not, however, be suddenly closed in the event of any person desiring to use them. {See also lavatory regulations.) [p.14]

Rates of pay:

Lavatory attendant (male) 4s a day and uniform

Lavatory attendant (female) 3s a day and uniform [p.36]

By the 1950s, there were at least two public conveniences on the Common (one near Baskerville Road, the other near Bolingbroke Grove on the other side of the London-Brighton railway).

[But why are there no lavatories in the area between West Side, North Side, Windmall Road and Spencer Park?

This was the subject of decades of argument between the Wandsworth Ratepayers Association (emphatically for), and other local agencies charged with building them (lukewarm or hostile). It's rather more than I can go into the moment, but interesting all the same. Perhaps another time.]

I must admit that I still get a slightly uncomfortable feeling walking past the rather gloomy site of the former loos just off the path near the pond.

I don't recall whether stories like the following were ever relayed to us (we probably wouldn't have read the item in the local newspapers but there might have been rumours), or they had any effect, but there was often a sense of risk in using the lavatories, or even walking near them.

For example, in the South Western Star of 17 January 1958 there was a short article beneath the headline "LONELY MAN FINED" (with a subhead, "WITHOUT FRIENDS"). It tells of a local man (he lived in St James's Drive) who was fined for "committing an act of gross indecency at a public convenience on Wandsworth Common".

He had been remanded in prison over Christmas but was now "ordered to pay a fine of £20 or four months' imprisonment in default". He avoided further imprisonment because "he had to use sticks and a wheel chair in order to get about".

"He was described as a lonely man without friends who roamed over Wandsworth Common striking up acquaintances with different people."

Chillingly, the article continues with a sentence within brackets: "(The other man concerned in the case committed suicide before his trial)".

hile we're on the subject of the siting of the loos, let's look at some "stink pipes" (aka "stench pipes" or, more politely, "vent stacks"), of which our area is so abundantly supplied.

In principle, these allowed noxious and smelly gases building up in the sewers to vent out and dissipate high above our heads. Some had a small door at the bottom for the insertion of lumps of carbon, designed to clean up the gases. Today, most stink pipes are cut in half — few survive to full height.

Do you know where this is on the Common?

Oh, what the heck. I can't resist posting some more fab pics of stink-pipes.Can you place them?

And this one?

And how about this beauty? The finest stink pipe I know of in the area, it's in a street in sight of the Common . . .

And finally . . .

More! More! Are there other stink-pipes or odd drains (and drain covers) on or near the Common? Let me know where you've found them — and ideally send me a photo to post here.

It's quite an irony that the need for the building of great sewers from the 1850s onwards was the proliferation of flushing lavatories. Until then, households used "earth closets" and cesspits, or paid to have their "night soil" carted away. But the new lavatories involved far too much effluent, hence new sewers were needed to carry it away to distant places (east of London) and thence into the Thames and the sea.

And there are several local connections.

For example, the amazing "Sewer King" Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891), who largely solved the problem, lived and died in Wimbledon — he is buried in the graveyard of St Mary's Church, whose great spire you can see from the Common.

But there are even closer connections. Both of the two main instigators of flushing loos — Thomas Crapper and George Jennings are both local men.

Thomas Crapper (1836-1910), probably the better known, lived on what is now called Buckmaster Road. I wrote about him at some length early last year.

— History of Wandsworth Common: Chronicles, January 2021: Thomas Crapper.

But in spite of his reputation, Crapper was not the "inventor" of the modern flush loo. A more compelling case can be made that it was George Jennings (1810-1882), a decade earlier. (See e.g. National Archives: Innovations in toilet design).

Jennings also designed and installed the first modern public lavatories at the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park (1851) and again in the Crystal Palace. The price to use the facilities was one penny, hence the euphemism "to spend a penny".

And George Jennings lived on Nightingale Lane.

How about that?

Expect more (much more) on George Jennings sometime in the future.Some acknowledgements

I am indebted for the Escritt quote about how aqueducts should be straight rather than curved to David Ainsworth of the Wandsworth Historical Society, formerly of the Wandsworth Local History Centre. He has also been most helpful in alerting me to possible lines of research — thanks, David!

He also recalled being contacted by a resident near St Anne's Church: "She had someone in doing some work (on her conservatory, I think), and he found something that his Kango hammer bounced off, so pretty hard concrete."

(I haven't looked at this in any detail, but I notice Bazalgette specifies the sewer should be made from granite blocks, York stone, and Portland concrete - so yes, probably pretty hard.)

Keith Bailey, doyen of building history in Battersea and Wandsworth, caused me to look more closely at maps

of the area around St Anne's Church — he is currently preparing an essay on the building history of Earlsfield.

Stephen Midlane, who is always interested in these things, sent some fab pics of stink pipes.

I would also like to thank Mike Tuffrey, historian of Clapham Common, for his invaluable support, including for introducing me to Marc Stchedroff, of the Oxford and London Basement Company. Marc is doing remarkable work on building studies in our area, and elsewhere. A recent piece, "King George’s Park nearly was the Down Estate & the Aqueduct", is closely related to this month's current Chronicles, and is terrific. But all his essays are chock-full of excellent material.

SO many more stories still to tell. But that's all for now, folks.

If you would like to receive occasional notifications of new Chronicles, let me know.

This search box is not very consistent, but always worth a try:

Send me an email if you enjoyed this post, or want to comment on something you've seen or read on the site, or would like to know more —or just want to be kept in touch.

August 2024

Return to the top of this page . . .