The disastrous Gallipoli Campaign took place from 25 April 1915 to 9 January 1916. Coates had been present when the first wounded troops arrived, probably mid-May 1915 — given how distant the battlefield in Turkey was from Britain, and the difficulties of transporting seriously injured men to London by ship, then train, then ship, then train, and finally by ambulance or car.

Phew, I made it! But only just. This month's Chronicles are even later than usual because I was working to the last minute on a talk for the Friends of Wandsworth Common, delivered on Monday 11 November as a contribution to the commemoration of Armistice Day. My subject was "Life and Death on Wandsworth Common: The Third London General Hospital, 1914-1921".

The wonderful John Crossland made a video of the talk, which you can view from the Friends of Wandsworth Common website, or here:

A number of people contacted me afterwards seeking further information, so I'm using these Chronicles to supplement the talk. Even so, there's far too much to reference here. But if you still have questions, please get in touch.

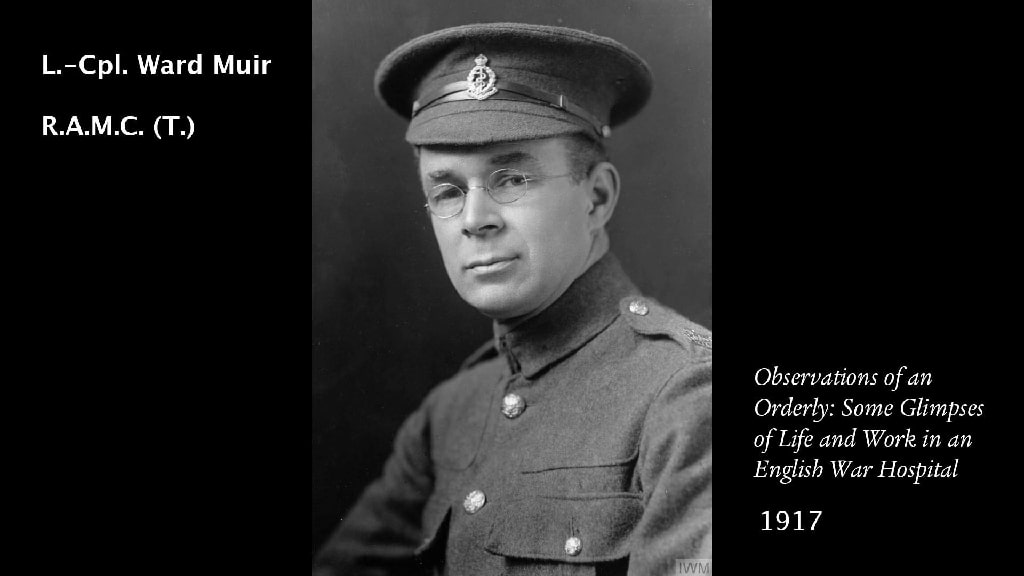

The main sources I used were the writings of Ward Muir, who was a Royal Army Medical Medical Corps Orderly from May 1915 to the end of the war. I can think of no better way of paying tribute to Ward Muir than by quoting him at some length, and pointing you towards some of his other essays and books.

Muir was one of a large (at least 25-strong) group of artists and writers recruited as orderlies from the Chelsea Arts Club, including George Coates, C.R.W Nevinson, and W.R.S. Stott, and the sculptor Frances Derwent Wood.

[Strictly speaking, Nevinson was not a member of the Club, but his friend Ward Muir, who was, thought he would fit in nicely with fellow artists — he didn't.]

Incidentally, Coates, Muir, Nevinson and Stott are commemorated in street names on the new-ish housing estate near the Patriotic Building:

Why these names were chosen, and by whom, I don't know. Can anyone clarify?

In my view, Bruce Porter, the Commanding Officer, should be commemorated, as should Matrons Eleanor Barton and Edith Holden.

Of the artists, James Henry Dowd's brilliant comic illustrations (mainly about "The Doings of Donovan") did more than anyone to raise morale. And what about Frances Derwent Wood, who used his skills as a sculptor to make masks to help facially disfigured soldiers?

And then there's Harry Fullwood, who painted the astonishing balloon-view over the 3rdLGH and Common in 1915?

That beef out of the way, at least for now, let's start with a chapter from Ward Muir's Observations of a Orderly: Some Glimpses at Life and Work in an English War Hospital (July 1917), which I think helps us to understand George Coates's painting better.

Muir describes a "huge room, with a lofty and echoing roof, a little in the style of a church" that's still in use today. It's been many other things since, but here is an image of its original incarnation, as the dining room of the Royal Victoria Patriotic Asylum for Girls.

Chapter VI — "When the Wounded Arrive"

CHAPTER VI

WHEN THE WOUNDED ARRIVE

THE receiving hall of the hospital is its clearing house of patients. It is a huge room, with a lofty and echoing roof, a little in the style of a church. Before the war, when the building was a school, this rather grandiose apartment no doubt witnessed speechifyings and prize distributions. May the time be not far distant when it will once again be used for those observances! Meanwhile its vast floor is occupied by ranks of beds.

Those beds are generally untenanted.

Visitors who, like the lady in the play, have taken the wrong turning, are apt to find themselves in the receiving hall, and, gazing at its array of vacant beds, have been known to conclude that the hospital was empty. (As if any war-hospital, in these times, could be empty!) But our patients have only a short acquaintanceship with the receiving-hall beds: these beds are momentary resting-places on their journey healthwards: they are not meant to lie in but to lie on.

The three-score wards for which the receiving hall is the clearing house are the real destination of the patients; down long corridors, in wards far cosier because less ornate than this, the patient will find "his" bed ready for him, the bed which he is not to lie on but in.

We orderlies meet each convoy at the front door of the hospital. The walking-cases are the first to arrive — men who are either not ill enough, or not badly enough wounded, to need to be put on stretchers in ambulances. They come from the station in motor-cars supplied by that indefatigable body, the London Ambulance Column. The walking-case alights from his car, is conducted into the receiving hall, and ten minutes later is in the bathroom.

For the ritual of the bath must on no account be omitted — although now not so obviously imperative as in the early period of the war. Few patients reach us who have not first sojourned, either for a day or two or for weeks, in hospitals in France.

They are therefore merely travel-stained, as you or I might be travel-stained after coming over from Dublin to Euston. The bath is thus a pleasure more than a necessity. Whereas there was an era, when our guests came straight from only too populous trenches . . .

"O.C. Baths," as the bathroom orderly was nicknamed, had to be circumspect in the performance of his job.

The few minutes which the walking-case spends in the receiving hall are occupied (1) in drinking a cup of cocoa, and (2) in "having his particulars taken." Poor soul! — he is weary of giving his "particulars." He has had to give them half-a-dozen times at least, perhaps more, since he left the front. At the field dressing-station they wanted his particulars, at the clearing-station, on the train, at the base hospital, on another train, on the steamer, on the next train, and now in this English hospital. As he sits and comforts himself with cocoa, a "V.A.D." [Voluntary Aid Detachment] hovers at his elbow, intent on a printed sheet, the details of which she is rapidly filling-in with a pencil.

For this is a card-index war, a colossal business of files and classifications and ledgers and statistics and registrations, an undertaking on a scale beside which Harrod's and Whiteley's and Selfridge's and Wanamaker's and the Magazin du Louvre, all rolled into one, would be a fleabite of simplicity.

Ere the morrow shall have dawned, our patient's military biography will be recounted, by various clerks, in I don't know how many different entries. If you are curious, refer to one of our volumes of the Admission and Discharge Book: Field Service Army Book 2ja. Open it at any of its closely-written pages and see the host of ruled columns which the orderly in charge of it must inscroll with reference to each of the many thousands of patients who pass through our hospital per annum.

The columns ask for his Regiment; Squadron, Battery or Company; Number; Rank; Surname; Christian Name; Age; Length of Service; Completed Months with Field Force; Diseases wounds and injuries are expressed by a number indicating their nature and whereabouts); Date of Admission; Date of Discharge or Transfer; Number of Days under Treatment; Number of Ward; Religion; and "Observations" a space usually occupied by the name of the hospital ship upon which our friend crossed the Channel, and the name of the convalescent home to which he went on bidding us adieu.

Having furnished the preliminary statements which lay the foundation of this compendious memoir, the walking-case thankfully finishes his cocoa, picks up the package of "blues" which has been put at his side, and departs, with his fellows, to the bathroom. Here he is tackled by the Pack Store orderlies, who take from him, and enter in their books, his khaki clothes. These he must leave in exchange for the blue slop uniform which, pro tem., is to be his only wear.

When he emerges from the bathroom he is attired in what is now England's most honourable livery — the royal blue of the war-hospital patient.

And (though perhaps the matter is not mentioned to him in so many words) his own suit is already ticketed with an identification label and on its way to the fumigator. This is no reflection on the owner of the suit . . . but there are some things we don't talk about. Mr. Fumigator-Wallah is not the least busy of the more retiring members of a war-hospital staff. He is not in the limelight; but you might come to be very sad and sorry if he took it into his head to neglect his unapplauded part off-stage.

The walking-cases are still splashing and dressing in the bathroom when the ambulances with the cot-cases begin to appear.

Now is the orderlies' busy time. Each stretcher must be quickly but gently removed from the ambulance and carried into the receiving hall.

Four orderlies haul the stretcher from its shelf in the ambulance; two orderlies then take its handles and carry it indoors.

At the entrance to the receiving hall they halt. The Medical Officer bends over the patient, glances at the label which is attached to him, and assigns him to a ward. (Certain types of cases go to certain groups of wards.) The attendant sergeant promptly picks a metal ticket from a rack and lays it on the stretcher. The ticket has, punched on it, the number of the patient's ward and the number of the patient's bed in that ward. This ceremony completed, the orderlies proceed, with their burden, up the aisle between the beds in the receiving hall.

Arrived at the bed, they lower their stretcher until it is at such a level that the patient, if he is active enough, can move off it on to the bed; if he is too weak to help himself he is lifted on to the bed by orderlies under the direction of the receiving-hall Sister. The stretcher is promptly removed and restored to its ambulance.

If the patient is in an exceptionally suffering condition he is not placed on the receiving-hall bed; instead, the Medical Officer having given his permission — his stretcher is put on a wheeled trolley and he is taken straight away to his ward, so that he will only undergo one shift of position between the ambulance and his destination.

The majority of stretcher-cases, however, reach us in a by no means desperate state, for, as I say, they seldom come to England without having been treated previously at a base abroad (except during the periods of heavy fighting). And it is remarkable how often the patient refuses help in getting off the stretcher on to the bed. He may be a cocoon of bandages, but he will courageously heave himself overboard, from stretcher to bed, with a gay wallop which would be deemed rash even in a person in perfect health.

Our receiving hall, at a big intake of wounded, when every bed bears its poor victim of the war, presents a spectacle which might give the philosopher food for thought; but I suspect that, if he regarded its actualities rather than his own preconceptions, what would impress him more than the sadness would be on the one hand the kindliness, brisk but not officious, of the staff, and on the other the spontaneous geniality of the battered occupants of the beds.

The orderlies can spare little time for talk, but the few chats which they are able to have with patients whom they are helping to change their clothes, or to whom they are proffering the inevitable cocoa (which is a cocktail, as it were, prior to the meal which will be served in the men's own ward), are punctuated by jokes and laughter rather than the long-visaged "sympathy" which the outsider might — quite wrongly! — have pictured as appropriate to such an assemblage.

The stretcher-case, before he is taken to his ward, must also "give his particulars, " must also be interviewed by the Store officials, and must also have assigned to him his blue uniform (wherewith are a shirt, a cravat, slippers and socks) in anticipation of the time when he shall be able to use his feet again and promenade our corridors and grounds. He receives the customary packet of cigarettes (probably the second, for he often gets one at the railway station too), and then, on another stretcher, mounted on a trolley, is wheeled off to his ward.

Here, bestowed in bed at last, we leave him to his blanket-bath, his meal, his temperature-taking and chart filling-in by the Sister, his visit from the doctor, and all the rest of it. For the moment we see no more of him; we must race back to the receiving hall, and, if there are no more patients to take away, return the trolley to its proper nook, put straight the blankets and pillows on the beds, sweep the floor, and tidy up generally, in readiness for the next convoy's advent.

Presently the huge room, beneath its dim arched ceiling, is silent and empty once more. The four ranks of beds, without a crease on their brown blankets, are bare of occupants. The Sister and her probationers have vanished. The Pack Store orderlies have carried off their loot of dirty khaki tunics and trousers for the fumigator. The clerical V.A.D.'s have gone to enter "particulars" in ledgers and card-indices. The cookhouse people have removed their cocoa urn.

The sergeant is inspecting the metal ward-tickets left in his rack. A glance at them tells him how many beds, and which beds, are free in the hospital; for the tickets have no duplicates; any given ticket can only reappear in the rack when the bed which it connotes is out of use and awaiting a newcomer; the ticket hangs from a nail in the wall beside the patient's bed just so long as that bed is tenanted. So the rack of metal tickets might almost take the place of that important document, of which a freshly-compiled edition is typed every morning, the Empty Bed List; and the sergeant is meditative as he sorts into the rack the tickets which have newly been sent in from the Sisters of wards where there have been departures. "Not much room in the eye-wound wards, " he ponders; or, "A lot of empties in the medicals." And then . . . the tinkle of the telephone . . . .

"Another convoy expected at 6.15? Twenty walking-cases and seventeen cots. Right you are!"

And at 6.15 the party of orderlies will be back again at the front door, again the motor-cars will stream up the drive, again the ambulances will come with their stretchers, and again the receiving hall will awaken from its interlude of silence to echo with the activities incidental to a clearing house of those damaged human bundles which are the raison d'etre of our great war-hospital.

In the fullness of time, I hope to transcribe and illustrate more of Ward Muir's marvellous essays from Observations of an Orderly:

I — MY FIRST DAY

II — LIFE IN THE ORDERLIES' HUTS

III — WASHING-UP

IV — A "HUT" HOSPITAL

V — FROM THE "D BLOCK" WARDS

VI — WHEN THE WOUNDED ARRIVE [above]

VII — T.... A....

VII — LAUNDRY PROBLEMS

IX — ON BUTTONS

X — A WORD ABOUT "SLACKERS IN KHAKI "

XI — THE RECREATION ROOMS

XII — THE COCKNEY

XIII — THE STATION PARTY

XIV — SLANG IN A WAR HOSPITAL

XV — A BLIND MAN'S HOME-COMING

And from Happy Hospital:

— NOTE ON HORRORS

— MASKS AND FACES

— "SISTER"

Extraordinary writing that deserves a wide readership.

The Gazette started with (I think) a print-run of 2000 copies, assuming that 3rd LGH patients and staff would be its principal audience. However it soon proved popular in and around Wandsworth, where it was sold in local shops and by such street sellers as "Gazette Girl" Eve.

With sales to family members all over the country, and to the "Dominions" (Australia, New Zealand and Canada were particularly important "markets" because about a half of the patients in the hospital were from there.

This also helps to explain why there are so many Commonwealth graves in Magdalen Road Cemetery.]

I'm not certain exactly what its maximum print run was, but it was least 5000 for local distribution, and possibly more for national and international postal distribution.

The cost per issue rose a number of times during the course of the war. Early editions cost 3d, or 4d if sent through the post. Visual appeal was such an important feature of the magazine that there was no skimping, but printing plates for artwork were more expensive than set text. Paper costs too rose steeply, so the price per copy rose again to 6d by 1919. The Gazette was "not for profit" — all money collected went into producing further copies, and into a fund for use in the hospital.

Many war hospitals around the country produced magazines and newsletters, but none (so far as I know) was anywhere near as successful as Wandsworth's Gazette — largely, I imagine, because of the professional skills of the editors (Ward Muir and Noel Irving) and the contributions of fine artwork from Chelsea Arts Club (and other) artists who had volunteered to work here. And then of course there was the enlightened encouragement of the Commanding Officer, Colonel Bruce Porter.

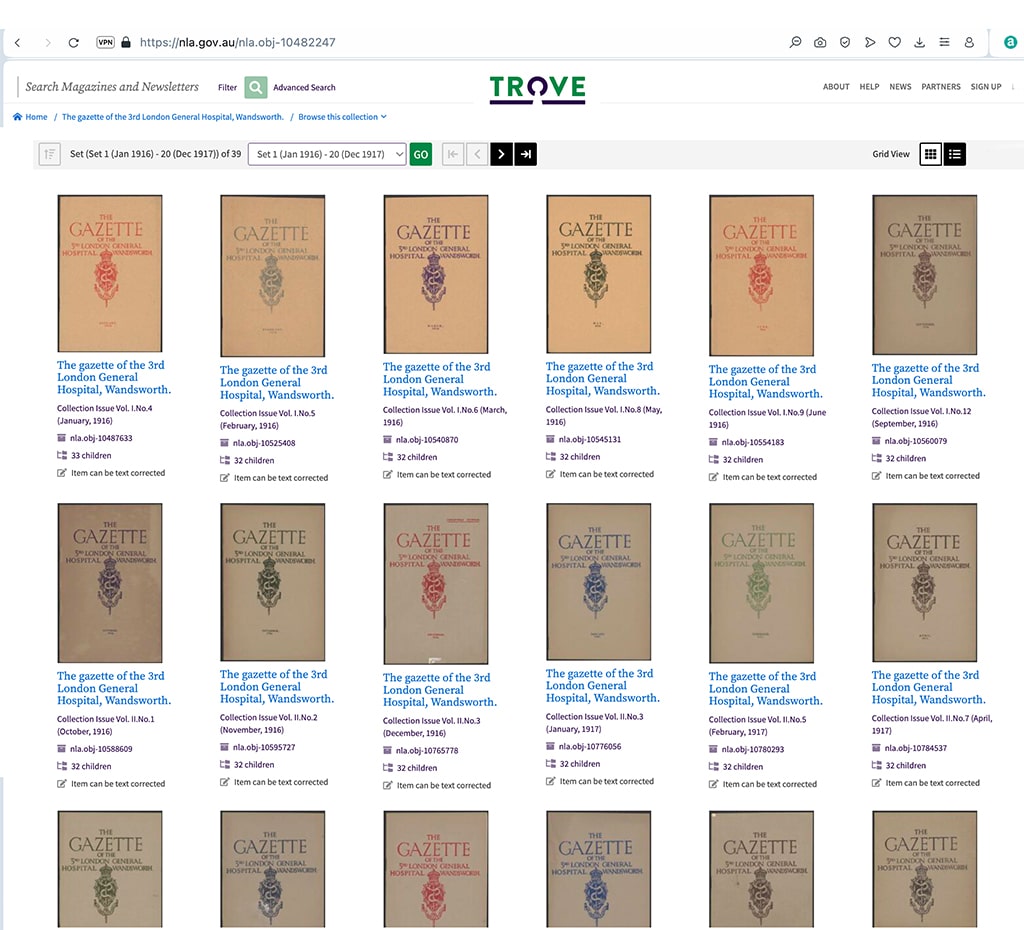

Several people have asked whether the Gazette is available online. It is.

Wellcome Collection, London — all issues, bound in 4 vols.

Trove, Australia — some issues are missing but the presentation of the issue separately and the transcriptions are very useful.

["Trove is a collaboration between the National Library of Australia and hundreds of Partner organisations around Australia."]

A number of people have asked about other war hospitals. The Royal Victoria Patriotic School was repurposed as the 3rd London General Hospital. Where were the other London General Hospitals? And did other local hospitals play a role?

Territorial Force Hospitals

In the country as a whole, there were 23 Territorial Hospitals, of which five were in London:

— 1st City of London General Hospital, Duke of York’s Headquarters, Chelsea.

— 2nd City of London General Hospital, St. Marks College, Chelsea.

— 3rd London General Hospital, Wandsworth Common.

— 4th London General Hospital, Denmark Hill, Camberwell. Formerly the Maudsley Memorial Hospital. By June 1918 it was known as Maudsley Neurological Clearing Hospital.

— 5th London General Hospital. Located at St Thomas’s Hospital.

Other local hospitals in the London Command District

— Bolingbroke Hospital, Bolingbroke Grove, Wandsworth Common

— Clapham Auxiliary Military Hospital, Cedars Road, Clapham

— Dover House, Roehampton

— Gifford House Auxiliary Hospital, Roehampton

— Perkins Bull Hospital for Convalescent Canadian Officers, Heathview Gardens, Putney

— Queen Mary's Convalescent Auxiliary Hospital, Roehampton

— St. James' Infirmary, St. James's Road [later Drive], Balham

— Springfield War Hospital, Beechcroft Road, Upper Tooting

— Streatham Relief Hospital, Streatham

— Templeton House Hospital, Roehampton

— The Grove Military Hospital, Tooting Grove, Tooting

— Tooting Military Hospital, Tooting

— Tooting Grove Military Hospital, London SW. A specialist venereal disease hospital.

— Weir Hospital, Grove Road, Balham.

[See Long Long Trail: Military Hospitals in the British Isles, and Lost Hospitals: Auxiliary Hospitals during WWI.]

This is not the well-known main building, from c.1840, but the "Annexe for Idiot Children", built c.1887 a hundred yards or so to the east. The Asylum as a whole was built as the Surrey Pauper Lunatic Asylum, but sold to Middlesex County Council c.1889 after new mental hospitals were built in the Surrey countryside.

From Lost Hospitals of London:

During WW1 the Asylum became the Springfield War Hospital. A Neurological Unit was established in the Annexe for Idiot Children, renamed Springfield House Hospital (separated from the main Asylum by a high fence) for patients with shell shock or loss of mental balance.

Together with the 4th London General Hospital [King's College Hospital, Denmark Hill], it was the principal reception centre for the mentally disabled from the front in France.

At the beginning of 1916 Springfield House Hospital accepted severe or protracted cases referred from the Neurological Units of the 23 Territorial Force General Hospitals in the United Kingdom."

[Lost Hospitals of London: Springfield University Hospital.

I am indebted to Stephen Bartley, Archivist at the Chelsea Arts Club, for his help in clarifying which 3rd LGH artists and writers were members. Thanks, Stephen!

I strongly recommend Pippa Sharp's essays published in the Wandsworth Historian:

— Pippa Sharp, "Chelsea Artist on the Wandsworth Salient", Wandsworth Historian, 98.

— Pippa Sharp, "Francis Derwent Wood and the Tin Nose Shop", Wandsworth Historian, 102.

[Incidentally, I believe Pippa lives locally. If you know her, do please send her a link to this month's Chronicles, and say I would very much like to be in touch.]

See Jean Davidson's deeply informed essays, again published in the Wandsworth Historian:

— "Five remarkable lives associated with the 3rd London General" Wandsworth Historian, 101. [Major Hugh Corbett Taylor Young, Australian surgeon; Frances Eileen Boyd, a VAD, and her husband Capt. Leslie Craig; Vernon Lorimer, illustrator; Albert Jacka, VC, MC.]

— "'He died an Australian hero, his duty nobly done’: the Australian war graves in Wandsworth Cemetery", Wandsworth Historian, 103.

If you are interested in doing further research on soldiers and nurses who died in the 3rd London General Hospital, please get in touch.

A note from Stephen Midlane, who convenes the Friends of Wandsworth Common Heritage Group:

An initiative by The Friends of Wandsworth Common meant that, in partnership with The Wandsworth Society, we recently managed to safeguard nearly 900 pictures of old Wandsworth for use by the local community.

The images, covering the Common and surrounding areas, were part of the very extensive Ron Elam postcard collection which was put up for sale at Toovey’s Auction House on 13th November.

Having acquired this wonderful collection, the next step is to scan and catalogue the images and then make them available to support a number of planned projects aimed at furthering our understanding of our local heritage.

Watch this space for more news soon!

Thanks, Stephen! Nine hundred pictures - fantastic news! I wrote a short piece about Ron, his fabulous collection, and the stall he used to set up on Bellevue Road every Saturday — it needs updating, but you can see it here.

I know a number of the pics in the new collection quite well, but many I've never seen before. The images haven't been scanned and catalogued yet, but here are snaps of just a few of them to give you a taste of the delights in store:

SO many more stories still to tell. But that's all for now, folks.

If you would like to receive occasional notifications of new Chronicles, let me know.

This search box is not very consistent, but always worth a try:

Send me an email if you enjoyed this post, or want to comment on something you've seen or read on the site, or would like to know more —or just want to be kept in touch.

November 2024

Return to the top of this page . . .